During the Great Migration, What Did the Term "Land of Hope" Refer to?

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

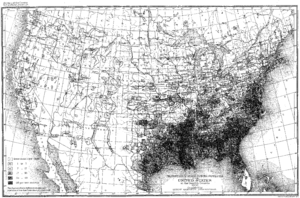

United States map of the Black American population from 1900 U.S. Census | |

| Engagement | 1916–1970 |

|---|---|

| Location | The states |

| Also known as | Great Northward Migration Blackness Migration |

| Cause | Poor economic weather condition Racial segregation in the United States:

|

| Participants | virtually 6,000,000 African Americans |

| Outcome | Demographic shifts across the U.Southward. Improved living conditions for African-Americans |

The Nifty Migration, sometimes known as the Great Due north Migration or the Blackness Migration, was the movement of 6 1000000 African Americans out of the rural Southern U.s. to the urban Northeast, Midwest and West that occurred after 1910, to 1970.[1] It was caused primarily by the poor economic weather for African American people, also as the prevalent racial segregation and discrimination in the Southern states where Jim Crow laws were upheld.[2] [3] In particular, connected lynchings motivated a portion of the migrants, equally African Americans searched for social reprieve. The celebrated change brought by the migration was amplified because the migrants, for the about part, moved to the so-largest cities in the United states of america (New York Metropolis, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C.) at a time when those cities had a cardinal cultural, social, political, and economic influence over the United States.[4] There, African Americans established influential communities of their ain.[four] Despite the loss of leaving their homes in the South, and all the barriers faced past the migrants in their new homes, the migration was an human action of private and collective bureau, which inverse the class of American history, a "proclamation of independence" written by their actions.[five]

From the earliest U.S. population statistics in 1780 until 1910, more than xc% of the African-American population lived in the American South,[6] [7] [8] making upwardly the majority of the population in three Southern states, viz. Louisiana (until well-nigh 1890[9]), S Carolina (until the 1920s[10]), and Mississippi (until the 1930s[11]). But past the end of the Groovy Migration, just over half of the African-American population lived in the Southward, while a little less than half lived in the North and West.[12] Moreover, the African-American population had become highly urbanized. In 1900, merely one-5th of African Americans in the S were living in urban areas.[13] Past 1960, half of the African Americans in the S lived in urban areas,[xiii] and by 1970, more than than fourscore% of African Americans nationwide lived in cities.[14] In 1991, Nicholas Lemann wrote:

The Great Migration was one of the largest and most rapid mass internal movements in history—perchance the greatest non caused past the firsthand threat of execution or starvation. In sheer numbers, information technology outranks the migration of any other ethnic group—Italians or Irish or Jews or Poles—to the United States. For Blackness people, the migration meant leaving what had ever been their economical and social base in America and finding a new one.[15]

Some historians differentiate between a first Great Migration (1910–xl), which saw about 1.6 1000000 people movement from mostly rural areas in the Southward to northern industrial cities, and a Second Bully Migration (1940–70), which began after the Great Depression and brought at to the lowest degree v million people—including many townspeople with urban skills—to the North and W.[sixteen]

Since the Civil Rights Movement, the trend has reversed, with more African-Americans moving to the South, albeit far more slowly. Dubbed the New Peachy Migration, these moves were generally spurred by the economic difficulties of cities in the Northeastern and Midwestern United states, growth of jobs in the "New Due south" and its lower toll of living, family and kinship ties, and lessening discrimination at the hands of white people.[17]

Causes [edit]

The Arthur family unit arrived at Chicago's Polk Street Depot on August 30, 1920, during the Smashing Migration.[18]

The primary factors for migration among southern African Americans were segregation, indentured servitude, convict leasing, an increment in the spread of racist credo, widespread lynching (nearly 3,500 African Americans were lynched between 1882 and 1968[xix]), and lack of social and economic opportunities in the Southward. Some factors pulled migrants to the north, such equally labor shortages in northern factories brought about by World State of war I, resulting in thousands of jobs in steel mills, railroads, meatpacking plants, and the automobile industry.[20] The pull of jobs in the due north was strengthened by the efforts of labor agents sent past northern businessmen to recruit southern workers.[xx] Northern companies offered special incentives to encourage Black workers to relocate, including free transportation and low-cost housing.[21]

During World War I, at that place was a decline in European immigrants, which caused Northern factories to feel the affect of a low supply of workers. Around 1.2 million European immigrants arrived during 1914 while only 300,000 arrived the next year. The enlistment of workers into the war machine had also affected the labor supply. This created a wartime opportunity in the Northward for African Americans, as the Northern industry sought a new labor supply in the South.[22]

There were many advantages for Northern jobs compared to Southern jobs including wages that could be double or more than. Sharecropping, agricultural depression, the widespread infestation of the boll weevil, and flooding besides provided motives for African Americans to move into the Northern Cities. The lack of political ability, representation, and social opportunities due to a culture regulated by Jim Crow laws also motivated African Americans to migrate Northward.[22]

Start Great Migration (1910–1940) [edit]

When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, less than eight percentage of the African-American population lived in the Northeastern or Midwestern United States.[23] This began to change over the next decade; by 1880, migration was underway to Kansas. The U.S. Senate ordered an investigation into information technology.[24] In 1900, about ninety percent of Blackness Americans however lived in Southern states.[23]

Between 1910 and 1930, the African-American population increased past near forty pct in Northern states every bit a result of the migration, by and large in the major cities. The cities of Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, Baltimore, and New York City had some of the biggest increases in the early part of the twentieth century. Tens of thousands of Black workers were recruited for industrial jobs, such as positions related to the expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Because changes were concentrated in cities, which had also attracted millions of new or recent European immigrants, tensions rose as the people competed for jobs and scarce housing. Tensions were oftentimes most astringent between ethnic Irish, defending their recently gained positions and territory, and recent immigrants and Black people.[ citation needed ]

Tensions and violence [edit]

With the migration of African Americans Northward and the mixing of White and Black workers in factories, the tension was edifice, largely driven by White workers. The AFL, the American Federation of Labor, advocated the separation between European Americans and African Americans in the workplace. There were non-tearing protests such as walk-outs in protest of having Blacks and Whites working together. As tension was building due to advocating for segregation in the workplace, violence soon erupted.[25]

In 1917, the East St Louis Illinois Riot, known for one of the bloodiest workplace riots, had betwixt 40 and 200 killed and over 6000 African Americans displaced from their homes. The NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, responded to the violence with a march known as the Silent March. Over 10,000 African American men and women demonstrated in Harlem, New York. Conflicts continued mail service World War I, as African Americans continued to face conflicts and tension while the African American labor activism continued.[25]

In the late summer and autumn of 1919, racial tensions became violent and came to be known as the Cherry Summer. This period of fourth dimension was defined by violence and prolonged rioting between Black and white Americans in major United states of america cities.[26] The reasons for this violence vary. Cities that were affected by the violence included Washington D.C., Chicago, Omaha, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Elaine, Arkansas, a pocket-size rural boondocks seventy miles (110 km) southwest of Memphis.[27]

The race riots peaked in Chicago, with the most violence and death occurring at that place during the riots.[28] The authors of The Negro in Chicago; a report of race relations and a race riot, an official study from 1922 on race relations in Chicago, came to the decision that there were many factors that led to the violent outbursts in Chicago. Principally, many Blackness workers had causeless the jobs of white men who went to go fight in World War I. As the war ended in 1918, many men returned abode to find out their jobs had been taken by Black men who were willing to work for far less.[27]

By the time the rioting and violence had subsided in Chicago, 38 people had lost their lives, with 500 more injured. Additionally, $250,000 worth of property was destroyed, and over a thousand persons were left homeless.[29] In other cities across the nation many more than had been afflicted by the violence of the Cerise Summer. The Blood-red Summer enlightened many to the growing racial tension in America. The violence in these major cities prefaced the soon to follow Harlem Renaissance, an African-American cultural revolution, in the 1920s.[28] Racial violence appeared again in Chicago in the 1940s and in Detroit also as other cities in the Northeast as racial tensions over housing and employment bigotry grew.

Continued migration [edit]

James Gregory calculates decade-by-decade migration volumes in his book The Southern Diaspora. Blackness migration picked upwardly from the start of the new century, with 204,000 leaving in the outset decade. The pace accelerated with the outbreak of Globe War I and continued through the 1920s. By 1930, there were 1.3 million former southerners living in other regions.[thirty] : 22

The Neat Depression wiped out job opportunities in the northern industrial belt, especially for African Americans, and caused a sharp reduction in migration. In the 1930s and 1940s, increasing mechanization of agriculture virtually brought the institution of sharecropping that had existed since the Civil War to an finish in the United States causing many landless Black farmers to exist forced off of the land.[31]

As a result, approximately 1.iv 1000000 Black southerners moved n or westward in the 1940s, followed by i.ane meg in the 1950s, and another 2.4 million people in the 1960s and early 1970s. By the tardily 1970s, equally deindustrialization and the Rust Belt crunch took hold, the Great Migration came to an finish. Only, in a reflection of changing economics, every bit well every bit the end of Jim Crow laws in the 1960s and improving race relations in the South, in the 1980s and early 1990s, more than Black Americans were heading Southward than leaving that region.[32] : 12–17

African Americans moved from the xiv states of the South, especially Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Georgia.[32] : 12

Second Great Migration (mid 1940s–1970) [edit]

The Smashing Depression of the 1930s resulted in reduced migration considering of decreased opportunities. With the defence buildup for World War Two and with the mail-war economic prosperity, migration was revived, with larger numbers of Black Americans leaving the S through the 1960s. This wave of migration often resulted in overcrowding of urban areas due to exclusionary housing policies meant to continue African American families out of developing suburbs.[ commendation needed ]

Migration patterns [edit]

Big cities were the principal destinations of southerners throughout the two phases of the Peachy Migration. In the first phase, eight major cities attracted two-thirds of the migrants: New York and Chicago, followed in order by Philadelphia, St. Louis, Denver, Detroit, Kansas City, Pittsburgh, and Indianapolis. The 2nd great Black migration increased the populations of these cities while adding others as destinations, including the Western states. Western cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Phoenix, Seattle, and Portland likewise managed to concenter African Americans in large numbers.[30] : 22

In that location were clear migratory patterns that linked particular states and cities in the South to corresponding destinations in the North and West. About half of those who migrated from Mississippi during the first Peachy Migration, for example, ended up in Chicago, while those from Virginia tended to move to Philadelphia. For the about part, these patterns were related to geography (i.e. longitude), with the closest cities attracting the near migrants (such as Los Angeles and San Francisco receiving a asymmetric number of migrants from Texas and Louisiana). When multiple destinations were equidistant, chain migration played a larger role, with migrants following the path set by those before them.[21]

African Americans from the Due south also migrated to industrialized Southern cities, in add-on to due north and westward to war-boom cities. There was an increase in Louisville's defense industries, making it a vital role of America's attempt into Earth War Two and Louisville's economy. Industries ranged from producing synthetic rubber, smokeless powders, artillery shells, and vehicle parts. Many industries also converted to creating products for the war effort, such as Ford Motor Company converting its plant to produce military jeeps. The company Hillerich & Bradsby, initially fabricated baseball bats and and so converted their product into making gunstocks.[33] [34]

During the state of war, at that place was a shortage of workers in the defense force industry. African Americans took the opportunity to fill in the industries' missing jobs during the war, around 4.three million intrastate migration and two.1 million interstate migration in the Southern states. The defense industry in Louisville reached a peak of roughly over eighty,000 employment. At kickoff, job availability was not open up for African Americans, but the growing need for jobs in the defense manufacture and the Fair Employment Practices Commission sign past Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Southern industries began to take African Americans into the workplace.[35] [34]

Migration patterns reflected network ties. Blackness Americans tended to go to locations in the Northward where other Black Americans had previously migrated. Per a 2021 study, "when one randomly called African American moved from a Southern birth town to a destination canton, then 1.ix additional Blackness migrants made the same move on boilerplate."[36]

Gallery [edit]

-

Graph showing the percentage of the African-American population living in the American South, 1790–2010

-

The Great Migration shown by changes in the African-American share of populations of major U.S. cities, 1910–xl and 1940–seventy

-

Racially motivated murders per decade from 1865 to 1965.

Cultural changes [edit]

After moving from the racist pressures of the s to the northern states, African Americans were inspired to different kinds of creativity. The Great Migration resulted in the Harlem Renaissance, which was also fueled by immigrants from the Caribbean area, and the Chicago Black Renaissance. In her book The Warmth of Other Suns, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson discusses the migration of "six million Black Southerners [moving] out of the terror of Jim Crow to an uncertain existence in the Due north and Midwest."[37]

The struggle of African-American migrants to adapt to Northern cities was the subject area of Jacob Lawrence's Migration Series of paintings, created when he was a young man in New York.[38] Exhibited in 1941 at the Museum of Modern Fine art, Lawrence'south Series attracted broad attending; he was apace perceived equally one of the most important African-American artists of the time.[39]

The Swell Migration had effects on music as well as other cultural subjects. Many dejection singers migrated from the Mississippi Delta to Chicago to escape racial bigotry. Muddy Waters, Chester Burnett, and Buddy Guy are amidst the nigh well-known blues artists who migrated to Chicago. Corking Delta-born pianist Eddie Boyd told Living Blues magazine, "I thought of coming to Chicago where I could get away from some of that racism and where I would have an opportunity to, well, practise something with my talent.... It wasn't peaches and foam [in Chicago], man, but it was a hell of a lot better than down there where I was built-in."[40]

Effects [edit]

Demographic changes [edit]

The Great Migration drained off much of the rural Black population of the Due south, and for a time, froze or reduced African-American population growth in parts of the region. The migration inverse the demographics in a number of states; at that place were decades of Blackness population decline, particularly across the Deep South "black chugalug" where cotton had been the main cash crop[32] : xviii — merely had been devastated by the arrival of the boll weevil.[41] In 1910, African Americans constituted the majority of the population of South Carolina and Mississippi, and more than than forty percent in Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana and Texas; by 1970, but in Mississippi did the African-American population constitute more than 30 percent of the state'due south total. "The disappearance of the 'blackness belt' was one of the striking effects" of the Great Migration, James Gregory wrote.[32] : xviii

In Mississippi, the Blackness American population decreased from almost 56% of the population in 1910 to almost 37% past 1970,[42] remaining the majority only in some Delta counties. In Georgia, Black Americans decreased from well-nigh 45% of the population in 1910 to about 26% by 1970. In South Carolina, the Blackness population decreased from almost 55% of the population in 1910 to about thirty% by 1970.[42]

The growing Black presence outside the Southward changed the dynamics and demographics of numerous cities in the Northeast, Midwest, and West. In 1900, just 740,000 African Americans lived exterior the Due south, only 8 per centum of the nation'due south total Black population. By 1970, more than 10.6 million African Americans lived exterior the South, 47 percent of the nation's full.[32] : 18

Considering the migrants concentrated in the large cities of the northward and due west, their influence was magnified in those places. Cities that had been virtually all white at the start of the century became centers of Blackness culture and politics by mid-century. Residential segregation and redlining led to concentrations of Black people in certain areas. The northern "Blackness metropolises" adult an of import infrastructure of newspapers, businesses, jazz clubs, churches, and political organizations that provided the staging ground for new forms of racial politics and new forms of Black culture.

Every bit a result of the Great Migration, the first large urban Blackness communities developed in northern cities beyond New York, Boston, Baltimore, Washington D.C., and Philadelphia, which had Black communities even earlier the Civil War, and attracted migrants subsequently the war. It is conservatively estimated that 400,000 African Americans left the South in 1916 through 1918 to have advantage of a labor shortage in industrial cities during the First World War.[43]

In 1910, the African-American population of Detroit was 6,000. The Great Migration, forth with immigrants from southern and eastern Europe as well as their descendants, apace turned the metropolis into the land's fourth-largest. By the kickoff of the Bang-up Low in 1929, the city's African-American population had increased to 120,000.

In 1900–01, Chicago had a total population of 1,754,473.[44] By 1920, the city had added more than than 1 million residents. During the second wave of the Great Migration (1940–60), the African-American population in the city grew from 278,000 to 813,000.

African-American youths play basketball in Chicago's Stateway Gardens loftier-ascension housing projection in 1973.

The catamenia of African Americans to Ohio, particularly to Cleveland, changed the demographics of the country and its primary industrial metropolis. Before the Peachy Migration, an estimated i.1% to 1.half dozen% of Cleveland's population was African American.[45] By 1920, 4.3% of Cleveland's population was African American.[45] The number of African Americans in Cleveland continued to rising over the next xx years of the Smashing Migration.

Other northeastern and midwestern industrial cities, such as Philadelphia, New York City, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Omaha, likewise had dramatic increases in their African-American populations. By the 1920s, New York's Harlem became a center of Black cultural life, influenced by the American migrants likewise every bit new immigrants from the Caribbean area.[46]

Second-tier industrial cities that were destinations for numerous Black migrants were Buffalo, Rochester, Boston, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Kansas Urban center, Columbus, Cincinnati, Grand Rapids and Indianapolis, and smaller industrial cities such as Chester, Gary, Dayton, Erie, Toledo, Youngstown, Peoria, Muskegon, Newark, Flint, Saginaw, New Oasis, and Albany. People tended to take the cheapest rail ticket possible and get to areas where they had relatives and friends.

For example, many people from Mississippi moved direct north by railroad train to Chicago, from Alabama to Cleveland and Detroit, from Georgia and South Carolina to New York City, Baltimore, Washington D.C. and Philadelphia, and in the second migration, from Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi to Oakland, Los Angeles, Portland, Phoenix, Denver, and Seattle.[ citation needed ]

Discrimination and working conditions [edit]

Educated African Americans were better able to obtain jobs after the Great Migration, eventually gaining a measure of form mobility, only the migrants encountered meaning forms of discrimination. Because and then many people migrated in a short menstruum of fourth dimension, the African-American migrants were ofttimes resented by the urban European-American working form (many of whom were contempo immigrants themselves); fearing their power to negotiate rates of pay or secure employment, the indigenous whites felt threatened past the influx of new labor contest. Sometimes those who were most fearful or resentful were the last immigrants of the 19th and new immigrants of the 20th century.[ commendation needed ]

African Americans made substantial gains in industrial employment, particularly in the steel, machine, shipbuilding, and meatpacking industries. Between 1910 and 1920, the number of Black workers employed in industry nearly doubled from 500,000 to 901,000.[43] Afterward the Groovy Low, more advances took identify later on workers in the steel and meatpacking industries organized into labor unions in the 1930s and 1940s, under the interracial Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The unions ended the segregation of many jobs, and African Americans began to advance into more than skilled jobs and supervisory positions previously informally reserved for whites.

Between 1940 and 1960, the number of Blackness people in managerial and authoritative occupations doubled, along with the number of Black people in white-neckband occupations, while the number of Black agricultural workers in 1960 barbarous to one-4th of what information technology was in 1940.[48] Too, betwixt 1936 and 1959, Black income relative to white income more than doubled in various skilled trades.[49] Despite employment discrimination,[50] Blackness people had college labor strength participation rates than whites in every U.S. Census from 1890 to 1950.[51] As a result of these advancements, the percentage of Black families living below the poverty line declined from 87 pct in 1940 to 47 percent past 1960 and to 30 percent by 1970.[52]

Populations increased so speedily among both African-American migrants and new European immigrants that at that place were housing shortages in most major cities. With fewer resources, the newer groups were forced to compete for the oldest, about run-downward housing. Ethnic groups created territories which they dedicated against alter. Discrimination often restricted African Americans to crowded neighborhoods. The more established populations of cities tended to move to newer housing as it was developing in the outskirts. Mortgage bigotry and redlining in inner city areas express the newer African-American migrants' power to determine their own housing, or obtain a fair cost. In the long term, the National Housing Deed of 1934 contributed to limiting the availability of loans to urban areas, particularly those areas inhabited by African Americans.[53]

Migrants going to Albany, New York found poor living conditions and employment opportunities, but also higher wages and better schools and social services. Local organizations such every bit the Albany Inter-Racial Quango and churches, helped them, but de facto segregation and discrimination remained well into the tardily 20th century.[54]

Migrants going to Pittsburgh and surrounding factory towns in western Pennsylvania between 1890 and 1930 faced racial discrimination and limited economic opportunities. The Black population in Pittsburgh jumped from vi,000 in 1880 to 27,000 in 1910. Many took highly paid, skilled jobs in the steel mills. Pittsburgh's Black population increased to 37,700 in 1920 (6.four% of the full) while the Blackness element in Homestead, Rankin, Braddock, and others nearly doubled. They succeeded in building effective customs responses that enabled the survival of new communities.[55] [56] Historian Joe Trotter explains the decision procedure:

- Although African-Americans often expressed their views of the Cracking Migration in biblical terms and received encouragement from northern Blackness newspapers, railroad companies, and industrial labor agents, they likewise drew upon family and friendship networks to assistance in the motion to Western Pennsylvania. They formed migration clubs, pooled their money, bought tickets at reduced rates, and ofttimes moved ingroups. Before they made the decision to move, they gathered data and debated the pros and cons of the process....In barbershops, poolrooms, and grocery stores, in churches, gild halls, and clubhouses, and in private homes, Black people who lived in the Southward discussed, debated, and decided what was skilful and what was bad about moving to the urban North.[57]

Integration and segregation [edit]

White tenants seeking to forestall Blackness people from moving into the Sojourner Truth housing project in Detroit erected this sign, 1942

In cities such as Newark, New York and Chicago, African Americans became increasingly integrated into society. As they lived and worked more closely with European Americans, the divide became increasingly indefinite. This period marked the transition for many African Americans from lifestyles equally rural farmers to urban industrial workers.[58]

This migration gave birth to a cultural boom in cities such as Chicago and New York. In Chicago for case, the neighborhood of Bronzeville became known as the "Black Metropolis". From 1924 to 1929, the "Black Metropolis" was at the superlative of its golden years. Many of the customs's entrepreneurs were Black during this period. "The foundation of the first African American YMCA took place in Bronzeville, and worked to aid incoming migrants find jobs in the metropolis of Chicago."[59]

The "Black Belt" geographical and racial isolation of this community, bordered to the north and east past whites, and to the due south and west by industrial sites and ethnic immigrant neighborhoods, made information technology a site for the report of the development of an urban Black community. For urbanized people, eating proper foods in a sanitary, civilized setting such as the domicile or a restaurant was a social ritual that indicated i's level of respectability. The people native to Chicago had pride in the high level of integration in Chicago restaurants, which they attributed to their unassailable manners and refined tastes.[60]

Since African-American migrants retained many Southern cultural and linguistic traits, such cultural differences created a sense of "otherness" in terms of their reception past others who were already living in the cities.[61] Stereotypes ascribed to Black people during this period and ensuing generations often derived from African-American migrants' rural cultural traditions, which were maintained in stark contrast to the urban environments in which the people resided.[61]

White southern reaction [edit]

The beginning of the Great Migration exposed a paradox in race relations in the American South at that fourth dimension. Although Black people were treated with farthermost hostility and subjected to legal discrimination, the southern economy was securely dependent on them equally an arable supply of inexpensive labor, and Black workers were seen as the most disquisitional cistron in the economic development of the South. I South Carolina politician summed upward the dilemma: "Politically speaking, there are far likewise many negroes, just from an industrial standpoint there is room for many more than."[62]

When the Great Migration started in the 1910s, white southern elites seemed to be unconcerned, and industrialists and cotton wool planters saw information technology as a positive, as it was siphoning off surplus industrial and agricultural labor. As the migration picked up, notwithstanding, southern elites began to panic, fearing that a prolonged Black exodus would bankrupt the Southward, and newspaper editorials warned of the danger. White employers somewhen took notice and began expressing their fears. White southerners before long began trying to stem the catamenia in gild to prevent the hemorrhaging of their labor supply, and some even began attempting to address the poor living standards and racial oppression experienced past Southern Blackness people in club to induce them to stay.

As a result, southern employers increased their wages to match those on offer in the North, and some individual employers even opposed the worst excesses of Jim Crow laws. When the measures failed to stem the tide, white southerners, in concert with federal officials who feared the rise of Black nationalism, co-operated in attempting to coerce Black people to stay in the Due south. The Southern Metal Trades Clan urged decisive action to stop Black migration, and some employers undertook serious efforts against it.[62] [63]

The largest southern steel manufacturer refused to cash checks sent to finance Black migration, efforts were made to restrict motorcoach and train admission for Blackness Americans, agents were stationed in northern cities to written report on wage levels, unionization, and the ascent of Blackness nationalism, and newspapers were pressured to divert more coverage to negative aspects of Black life in the North. A series of local and federal directives were put into place with the goal of restricting Black mobility, including local vagrancy ordinances, "work or fight" laws demanding all males either exist employed or serve in the army, and conscription orders. Intimidation and beatings were also used to terrorize Black people into staying.[62] [63] These intimidation tactics were described by Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson every bit interfering with "the natural right of workers to motion from place to identify at their ain discretion".[64]

During the moving ridge of migration that took place in the 1940s, white southerners were less concerned, as mechanization of agronomics in the late 1930s had resulted in some other labor surplus and so southern planters put up less resistance.[62]

Black Americans were non the only group to leave the South for Northern industrial opportunities. Big numbers of poor whites from Appalachia and the Upland Due south made the journeying to the Midwest and Northeast later Earth War Two, a phenomenon known every bit the Hillbilly Highway.

In pop culture [edit]

The Bully Migration is a backdrop of the 2013 moving picture The Butler, as the Forest Whitaker graphic symbol Cecil Gaines moves from a plantation in Georgia to become a butler at the White House.[65] The Great Migration likewise served equally part of Baronial Wilson's inspiration for The Pianoforte Lesson.[66]

Statistics [edit]

| Region | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | Alter in the Black Percentage of the Full Population Between 1900 and 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | 11.half-dozen% | 10.7% | nine.nine% | 9.7% | 9.eight% | x.0% | 10.5% | 11.one% | 11.7% | +0.1% |

| Northeast | 1.viii% | 1.9% | 2.3% | iii.3% | iii.8% | 5.1% | half-dozen.8% | 8.9% | nine.nine% | +eight.1% |

| Midwest | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.3% | three.iii% | 3.5% | 5.0% | 6.vii% | 8.i% | 9.1% | +7.ii% |

| South | 32.three% | 29.8% | 26.9% | 24.7% | 23.8% | 21.7% | 20.6% | 19.1% | 18.vi% | -19.7% |

| West | 0.seven% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.ii% | 2.ix% | iii.9% | 4.ix% | five.2% | +four.v% |

| Country | Region | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | Modify in the Black Percentage of the Total Population Between 1900 and 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | N/A | 11.6% | 10.7% | nine.9% | 9.7% | 9.8% | 10.0% | ten.5% | 11.ane% | 11.seven% | +0.1% |

| | S | 45.two% | 42.five% | 38.iv% | 35.seven% | 34.7% | 32.0% | xxx.0% | 26.2% | 25.6% | -xix.6% |

| | West | 0.3% | 0.iii% | 0.ii% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 3.0% | 3.0% | three.4% | +3.ane% | |

| | Due west | 1.v% | 1.0% | 2.four% | 2.five% | three.0% | 3.v% | 3.three% | 3.0% | 2.8% | +1.3% |

| | South | 28.0% | 28.ane% | 27.0% | 25.8% | 24.8% | 22.3% | 21.8% | 18.3% | 16.iii% | -xi.ii% |

| | West | 0.7% | 0.9% | one.1% | 1.4% | 1.viii% | 4.4% | v.6% | 7.0% | 7.7% | +six.0% |

| | West | i.6% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.one% | ane.1% | ane.v% | 2.3% | 3.0% | 3.v% | +one.9% |

| | Northeast | i.7% | i.4% | 1.5% | 1.8% | 1.nine% | two.7% | 4.2% | 6.0% | 7.0% | +half dozen.3% |

| | South | 16.6% | 15.4% | 13.six% | thirteen.7% | 13.five% | thirteen.7% | 13.vi% | 14.iii% | 16.1% | -0.v% |

| | South | 31.one% | 28.five% | 25.1% | 27.1% | 28.two% | 35.0% | 53.9% | 71.i% | lxx.3% | +38.2% |

| | South | 43.7% | 41.0% | 34.0% | 29.4% | 27.1% | 21.8% | 17.8% | fifteen.3% | 13.8% | -29.9% |

| | South | 46.7% | 45.i% | 41.7% | 36.viii% | 34.7% | 30.nine% | 28.5% | 25.9% | 26.eight% | -16.2% |

| | West | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.ane% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.8% | +i.6% |

| | West | 0.two% | 0.2% | 0.ii% | 0.ii% | 0.ane% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.three% | +0.ane% |

| | Midwest | i.8% | 1.9% | ii.viii% | iv.3% | 4.9% | 7.4% | 10.three% | 12.viii% | 14.seven% | +12.9% |

| | Midwest | 2.iii% | 2.two% | 2.8% | 3.5% | 3.half dozen% | 4.4% | 5.viii% | 6.9% | 7.6% | +v.3% |

| | Midwest | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.eight% | 0.9% | i.2% | ane.four% | +1.2% |

| | Midwest | three.v% | 3.ii% | 3.iii% | 3.5% | 3.6% | three.8% | 4.2% | 4.8% | five.iii% | +1.viii% |

| | S | thirteen.3% | 11.4% | 9.8% | 8.half dozen% | vii.5% | 6.9% | 7.1% | vii.ii% | seven.1% | -6.2% |

| | South | 47.ane% | 43.1% | 38.ix% | 36.9% | 35.ix% | 32.9% | 31.9% | 29.viii% | 29.iv% | -17.seven% |

| | Northeast | 0.two% | 0.2% | 0.ii% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.i% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | +0.1% |

| | S | nineteen.8% | 17.nine% | 16.ix% | 16.9% | sixteen.6% | sixteen.5% | xvi.7% | 17.8% | 22.7% | +1.9% |

| | Northeast | i.1% | 1.1% | 1.2% | ane.ii% | 1.3% | 1.6% | 2.ii% | 3.1% | 3.ix% | +two.8% |

| | Midwest | 0.7% | 0.6% | 1.half dozen% | iii.5% | four.0% | six.9% | 9.2% | 11.2% | 12.9% | +12.2% |

| | Midwest | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.iv% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.seven% | 0.ix% | one.3% | +1.0% |

| | Southward | 58.5% | 56.2% | 52.2% | l.2% | 49.2% | 45.iii% | 42.0% | 36.8% | 35.two% | -23.3% |

| | Midwest | 5.2% | 4.eight% | 5.2% | 6.2% | six.five% | seven.5% | 9.0% | x.three% | x.5% | +5.3% |

| | West | 0.half-dozen% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.ii% | 0.ii% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.two% | -0.four% |

| | Midwest | 0.half-dozen% | 0.6% | 1.0% | 1.0% | i.i% | one.5% | 2.1% | ii.seven% | 3.1% | +2.v% |

| | W | 0.3% | 0.six% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 2.seven% | 4.vii% | v.7% | six.4% | +vi.1% |

| | Northeast | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.three% | 0.3% | 0.4% | +0.2% |

| | Northeast | 3.7% | 3.5% | three.vii% | five.2% | 5.v% | half dozen.6% | 8.five% | 10.7% | 12.6% | +9.nine% |

| | West | 0.8% | 0.5% | 1.6% | 0.7% | 0.nine% | 1.two% | 1.eight% | 1.9% | ane.8% | +ane.0% |

| | Northeast | one.4% | 1.5% | 1.9% | 3.three% | 4.2% | half dozen.two% | 8.four% | 11.ix% | 13.7% | +12.3% |

| | South | 33.0% | 31.six% | 29.viii% | 29.0% | 27.5% | 25.8% | 24.5% | 22.ii% | 22.4% | -10.6% |

| | Due west | 0.1% | 0.one% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.i% | 0.4% | 0.four% | +0.iii% |

| | Midwest | 2.three% | two.3% | iii.2% | 4.7% | 4.9% | six.5% | 8.1% | 9.1% | 10.0% | +seven.vii% |

| | S | 7.0% | 8.3% | vii.4% | seven.2% | 7.2% | six.v% | 6.6% | 6.7% | half dozen.8% | -0.two% |

| | W | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.iv% | +ane.1% |

| | Northeast | 2.5% | 2.five% | 3.three% | 4.5% | four.vii% | six.one% | 7.5% | eight.6% | viii.8% | +6.3% |

| | Northeast | two.1% | 1.8% | 1.vii% | 1.4% | 1.5% | i.eight% | 2.1% | 2.7% | ii.9% | +0.8% |

| | South | 58.4% | 55.ii% | 51.4% | 45.6% | 42.9% | 38.8% | 34.8% | xxx.5% | 30.iv% | -28.0% |

| | Westward | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.i% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | +0.2% |

| | South | 23.viii% | 21.7% | 19.3% | eighteen.3% | 17.4% | 16.1% | sixteen.5% | 15.8% | xv.8% | -8.0% |

| | Southward | twenty.4% | 17.seven% | xv.9% | 14.7% | 14.4% | 12.7% | 12.4% | 12.five% | 12.0% | -viii.0% |

| | Westward | 0.ii% | 0.three% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.vi% | 0.half dozen% | +0.4% |

| | Northeast | 0.two% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.ane% | 0.1% | 0.ane% | 0.two% | 0.two% | +0.0% |

| | South | 35.vi% | 32.6% | 29.9% | 26.eight% | 24.7% | 22.ane% | xx.6% | xviii.five% | xviii.9% | -xvi.vii% |

| | West | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 1.3% | 1.seven% | 2.1% | 2.6% | +two.1% |

| | Southward | 4.5% | five.3% | v.ix% | half-dozen.6% | half-dozen.2% | five.seven% | iv.viii% | 3.ix% | 3.3% | -1.2% |

| | Midwest | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.ii% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.eight% | 1.9% | two.9% | 3.nine% | +3.8% |

| | Due west | one.0% | 1.5% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.ix% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.7% | -0.3% |

| Metropolis | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | Modify in the Black Per centum of the Full Population Betwixt 1900 and 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenix, Arizona | two.7% | 2.ix% | 3.seven% | 4.9% | 6.5% | iv.9% | 4.8% | 4.8% | four.viii% | 5.2% | +ii.v% |

| Los Angeles, California | 2.ane% | 2.4% | 2.7% | 3.1% | iv.two% | viii.7% | 13.5% | 17.9% | 17.0% | 14.0% | +11.nine% |

| San Diego, California | 1.eight% | i.5% | i.3% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 4.5% | half dozen.0% | 7.half dozen% | 8.nine% | 9.four% | +7.6% |

| San Francisco, California | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.half-dozen% | 0.8% | v.6% | 10.0% | thirteen.iv% | 12.7% | ten.9% | +10.iv% |

| San Jose, California | 1.0% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.half dozen% | one.0% | 2.5% | 4.6% | 4.vii% | +3.seven% |

| Denver, Colorado | 2.ix% | two.5% | two.4% | two.5% | 2.4% | 3.six% | half-dozen.ane% | 9.1% | 12.0% | 12.8% | +nine.nine% |

| Washington, Commune of Columbia | 31.1% | 28.5% | 25.1% | 27.one% | 28.ii% | 35.0% | 53.nine% | 71.1% | 70.3% | 65.8% | +34.7% |

| Chicago, Illinois | 1.8% | ii.0% | 4.i% | 6.9% | 8.ii% | xiii.6% | 22.9% | 32.vii% | 39.8% | 39.ane% | +37.3% |

| Indianapolis, Indiana | nine.4% | 9.3% | 11.0% | 12.one% | 13.two% | 15.0% | xx.half dozen% | 18.0% | 21.eight% | 22.half dozen% | +13.2% |

| Baltimore, Maryland | 15.six% | 15.2% | 14.8% | 17.7% | 19.iii% | 23.7% | 34.7% | 46.4% | 54.viii% | 59.2% | +43.6% |

| Boston, Massachusetts | 2.one% | 2.0% | 2.2% | two.6% | 3.i% | 5.0% | 9.one% | 16.3% | 22.iv% | 25.half-dozen% | +23.v% |

| Detroit, Michigan | 1.4% | 1.2% | 4.1% | 7.seven% | 9.2% | 16.2% | 28.9% | 43.7% | 63.i% | 75.7% | +74.3% |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 0.8% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.3% | 2.4% | 4.iv% | 7.7% | xiii.0% | +12.ii% |

| Kansas City, Missouri | 10.seven% | 9.5% | nine.v% | 9.6% | 10.4% | 12.two% | 17.5% | 22.one% | 27.4% | 29.6% | +eighteen.9% |

| St. Louis, Missouri | half-dozen.2% | 6.4% | 9.0% | eleven.4% | 13.3% | 17.9% | 28.half-dozen% | 40.9% | 45.vi% | 47.five% | +41.3% |

| Buffalo, New York | 0.five% | 0.four% | 0.9% | ii.4% | three.one% | six.3% | 13.3% | twenty.4% | 26.6% | 30.7% | +30.2% |

| New York, New York | 1.8% | ane.9% | 2.7% | iv.7% | vi.1% | ix.5% | fourteen.0% | 21.1% | 25.2% | 28.seven% | +26.9% |

| Cincinnati, Ohio | 4.iv% | 5.4% | 7.v% | 10.6% | 12.ii% | 15.v% | 21.6% | 27.6% | 33.8% | 37.9% | +33.5% |

| Cleveland, Ohio | 1.6% | i.v% | four.3% | 8.0% | 9.six% | xvi.2% | 28.6% | 38.3% | 43.8% | 46.half dozen% | +45.0% |

| Columbus, Ohio | 6.5% | 7.0% | 9.4% | 11.three% | 11.7% | 12.4% | sixteen.4% | eighteen.5% | 22.one% | 22.6% | +16.i% |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | four.viii% | 5.five% | 7.4% | xi.3% | 13.0% | 18.two% | 26.4% | 33.6% | 37.8% | 39.9% | +35.ane% |

| Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | 5.iii% | 4.viii% | half-dozen.4% | 8.two% | ix.3% | 12.two% | 16.7% | 20.2% | 24.0% | 25.8% | +xx.v% |

| Seattle, Washington | 0.five% | ane.0% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 3.4% | 4.8% | 7.1% | 9.v% | ten.one% | +9.half dozen% |

| Milwaukee, Wisconsin | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 1.3% | 1.v% | iii.4% | 8.4% | xiv.7% | 23.ane% | xxx.5% | +xxx.two% |

| City | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | Change in the Black Percentage of the Total Population Between 1900 and 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jacksonville, Florida | 57.1% | 50.8% | 45.iii% | 37.ii% | 35.seven% | 35.4% | 41.1% | 22.three% | 25.4% | 25.2% | -31.9% |

| New Orleans, Louisiana | 27.1% | 26.three% | 26.one% | 28.3% | 30.1% | 31.9% | 37.2% | 45.0% | 55.three% | 61.9% | +34.8% |

| Memphis, Tennessee | 48.8% | 40.0% | 37.7% | 38.1% | 41.5% | 37.ii% | 37.0% | 38.9% | 47.vi% | 54.viii% | +6.0% |

| Dallas, Texas | 21.two% | 19.half-dozen% | xv.1% | xiv.9% | 17.1% | 13.1% | xix.0% | 24.9% | 29.iv% | 29.5% | +viii.iii% |

| El Paso, Texas | 2.nine% | 3.7% | i.seven% | 1.8% | ii.3% | 2.four% | two.1% | two.3% | 3.2% | 3.4% | +0.5% |

| Houston, Texas | 32.7% | 30.4% | 24.six% | 21.7% | 22.four% | 20.9% | 22.nine% | 25.vii% | 27.6% | 28.1% | -iv.6% |

| San Antonio, Texas | 14.ane% | eleven.1% | eight.9% | 7.viii% | 7.6% | seven.0% | 7.1% | 7.half-dozen% | 7.3% | vii.0% | -7.i% |

-

A map of the blackness percentage of the U.S. population past each state/territory in 1900.

Black = 35.00+%

Brown = xx.00-34.99%

Red = 10.00-19.99%

Orange = five.00-nine.99%

Light orange = one.00-four.99%

Gray = 0.99% or less

Magenta = No information bachelor -

A map of the black percentage of the U.Due south. population by each country/territory in 1990.

Blackness = 35.00+%

Brownish = 20.00–34.99%

Blood-red = 10.00–19.99%

Orange = five.00–ix.99%

Light orange = 1.00–four.99%

Grey = 0.99% or less

Pink = No information available -

A map showing the change in the full Black population (in pct) between 1900 and 1990 by U.S. state.

Light imperial = Population turn down

Very light light-green = Population growth of 0.01–9.99%

Low-cal green = Population growth of 10.00–99.99%

Green = Population growth of 100.00–999.99%

Dark green = Population growth of i,000.00–nine,999.99%

Very dark greenish (or Blackness) = Population growth of 10,000.00% or more

Magenta = No data available

New Peachy Migration [edit]

Afterwards the political and civil gains of the Ceremonious Rights Movement, in the 1970s migration began to increase again. Information technology moved in a different direction, as Black people traveled to new regions of the Southward for economic opportunity.[72] [73]

See too [edit]

- 1912 Racial Conflict of Forsyth County, Georgia

- Exodusters

- Historical racial and indigenous demographics of the United States

- White flight

- Living for the City

- Hillbilly Highway

- Urban Appalachians

- African American settlements in Western Canada

- Back to Africa movement

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ https://www.archives.gov/enquiry/african-americans/migrations/great-migration

- ^ "The Great Migration" (PDF). Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel. "The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration". Smithsonian . Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Gregory, James. "Black City". America's Great Migrations Projects. University of Washington. Retrieved March 25, 2021. (with excepts from, Gregory, James. The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America, Affiliate iv: Black Metropolis (University of North Carolina Press, 2005)

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel (September 2016). "The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Neat Migration". Smithsonian Magazine . Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–129. ISBN978-0816025275.

- ^ "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics" (PDF). The states Demography Bureau. p. 1168.

- ^ Gibson, Campbell; Jung, Kay (September 2002). HISTORICAL CENSUS STATISTICS ON POPULATION TOTALS BY RACE, 1790 TO 1990, AND BY HISPANIC ORIGIN, 1970 TO 1990, FOR THE UNITED STATES, REGIONS, DIVISIONS, AND STATES (PDF) (Study). Population Division Working Papers. Vol. 56. United states Demography Bureau.

- ^ "Table 33. Louisiana – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1810 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February seven, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "Table 39. Mississippi – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1800 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "The Second Bully Migration", The African American Migration Experience, New York Public Library, archived from the original on March 12, 2020, retrieved Jan 17, 2017

- ^ a b Taeuber, Karl E.; Taeuber, Alma F. (1966), "The Negro Population in the United states of america", in Davis, John P. (ed.), The American Negro Reference Book, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, p. 122

- ^ "The Second Cracking Migration", The African American Migration Experience, New York Public Library, archived from the original on March 12, 2020, retrieved March 23, 2016

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (1991). The Promised Country: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 6. ISBN0-394-56004-3.

- ^ Frey, William H. (May 2004). "The New Bang-up Migration: Blackness Americans' Return to the Due south, 1965–2000". The Brookings Institution. pp. ane–3. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved March nineteen, 2008.

- ^ Reniqua Allen (July 8, 2017). "Racism Is Everywhere, So Why Not Move South?". The New York Times . Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ Glanton, Dahleen (July 13, 2020). "Returning South: A family unit revisits a double lynching that forced them to flee to Chicago 100 years ago". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ "Lynchings: Past Country and Race, 1882–1968". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on June 29, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

- ^ a b Hine, Darlene; Hine, William; Harrold, Stanley (2012). African Americans: A Concise History (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 388–389. ISBN978-0-205-80627-0.

- ^ a b Kopf, Dan (Jan 28, 2016). "The Great Migration: The African American Exodus from The South". Priceonomics . Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Arnesen, Eric. (2003). Black protest and the great migration : a cursory history with documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin'due south. pp. 2–11. ISBN0-312-39129-iii. OCLC 51099552.

- ^ a b Census, Usa Bureau of the (July 23, 2010). "Migrations – The African-American Mosaic Exhibition – Exhibitions (Library of Congress)". world wide web.loc.gov.

- ^ "Exodus to Kansas". August 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Arnesen, Eric. (2003). Black protest and the bang-up migration : a brief history with documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin'south. pp. 12–fifteen, 29–35. ISBN0-312-39129-3. OCLC 51099552.

- ^ Broussard, Albert South. (Spring 2011). "New Perspectives on Lynching, Race Riots, and Mob Violence". Journal of American Ethnic History. 30 (3): 71–75. doi:ten.5406/jamerethnhist.xxx.3.0071 – via EBSCO.

- ^ a b Chicago Commission on Race Relations. The Negro in Chicago: A Study in Race Relations and a Race Riot in 1919. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1922.

- ^ a b "Chicago Race Riot of 1919." Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., n.d. Web. May 20, 2017.<https://www.britannica.com/event/Chicago-Race-Riot-of-1919>.

- ^ Drake, St. Claire; Cayton, Horace R. (1945). Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City. USA: Harcourt, Caryatid and Company. p. 65.

- ^ a b Gregory, James N. (2009) "The Second Great Migration: An Historical Overview," African American Urban History: The Dynamics of Race, Grade, and Gender since Earth War Ii, eds. Joe Due west. Trotter Jr. and Kenneth L. Kusmer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- ^ Gordon Marshall, "Sharecropping," Encyclopedia.com, 1998.

- ^ a b c d e Gregory, James Northward. (2005). The Southern Diaspora: How the Corking Migrations of Blackness and White Southerners Transformed America. Chapel Hill: Academy of Due north Carolina Press. ISBN978-0-8078-5651-two.

- ^ Adams, Luther. (2010). Manner up north in Louisville : African American migration in the urban South, 1930-1970. Chapel Loma: Academy of Due north Carolina Press. pp. 24–36. ISBN978-0-8078-9943-4. OCLC 682621088.

- ^ a b Lundberg, Terri (January 28, 2014). "Black History in Kansas City". Black Chick On Tour . Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ Adams, Luther. (2010). Mode upwards due north in Louisville : African American migration in the urban S, 1930-1970. Chapel Hill: University of Northward Carolina Press. pp. 24–36. ISBN978-0-8078-9943-4. OCLC 682621088.

- ^ Stuart, Bryan A.; Taylor, Evan J. (2021). "Migration Networks and Location Decisions: Prove from US Mass Migration". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 13 (3): 134–175. doi:10.1257/app.20180294. hdl:10419/207533. ISSN 1945-7782. S2CID 141068688.

- ^ "Review: The Warmth of Other Suns: The Ballsy Story of America'south Great Migration". Publishers Weekly. September 2010. Retrieved Baronial 16, 2015.

- ^ world wide web.sbctc.edu (adjusted). "Module 1: Introduction and Definitions" (PDF). Saylor.org. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (June 10, 2000). "Jacob Lawrence Is Expressionless at 82; Brilliant Painter Who Chronicled Odyssey of Black Americans". The New York Times . Retrieved June xv, 2018.

- ^ David P. Szatmary, Rockin' in Time, eighth ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2014), p. viii

- ^ Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem; Obstfeld, Raymond (2007). On The Shoulders Of Giants : My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 1–288. ISBN978-i-4165-3488-iv. OCLC 76168045.

- ^ a b Gibson, Campbell and Kay Jung (September 2002). Historical Demography Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and Past Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The Us, Regions, Divisions, and States. Archived December 24, 2014, at the Wayback Auto U.S. Agency of the Census – Population Division.

- ^ a b James Gilbertlove, "African Americans and the American Labor Movement", Prologue, Summer 1997, Vol. 29.

- ^ Gibson, Campbell (June 1998). Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990 Archived March 14, 2007, at the Wayback Auto. U.S. Bureau of the Census – Population Division.

- ^ a b Gibson, Campbell, and Kay Jung. "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and past Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for Large Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States." U.S. Demography Bureau, February 2005.

- ^ Hutchinson, George (August 19, 2020). "Harlem Renaissance". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved February xix, 2021.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ A Brief Await at The Bronx, Bronx Historical Society. Accessed September 23, 2007. Archived August vii, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Miller, Aurelia Toyer (1980). "The Social and Economic Status of the Blackness Population in the U.Due south.: An Historical View, 1790–1978". The Review of Blackness Political Economy. 10 (3): 314–318. doi:10.1007/bf02689658. S2CID 153619673.

- ^ Ashenfelter, Orley (1970). "Changes in Labor Market Discrimination Over Time". The Journal of Human Resources. 5 (iv): 403–430. doi:10.2307/144999. JSTOR 144999.

- ^ Thernstrom, Stephan (1973). The Other Bostonians: Poverty and Progress in the American Metropolis, 1880–1970. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 201. ISBN978-0674433946.

- ^ Historical Statistics of the United States: From Colonial Times to 1957 (Study). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, U.Southward. Government Printing Office. 1960. p. 72.

- ^ Thernstrom, Stephan; Thernstrom, Abigail (1997). America in Black and White: I Nation, Indivisible. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 232. ISBN978-0684809335.

- ^ Gotham, Kevin Fox (2000). "Racialization and the State: The Housing Act of 1934 and the Creation of the Federal Housing Administration". Sociological Perspectives. 43 (two): 291–317. doi:10.2307/1389798. JSTOR 1389798. S2CID 144457751.

- ^ Lemak, Jennifer A. (2008). "Albany, New York and the Great Migration". Afro-Americans in New York Life and History. 32 (ane): 47.

- ^ Joe W. Trotter, "Reflections on the Great Migration to Western Pennsylvania." Western Pennsylvania History (1995) 78#4: 153-158 online.

- ^ Joe W. Trotter, and Eric Ledell Smith, eds. African Americans in Pennsylvania: Shifting Historical Perspectives (Penn Land Printing, 2010).

- ^ Trotter, "Reflections on the Not bad Migration to Western Pennsylvania," p 154.

- ^ Black exodus : the swell migration from the American South. Harrison, Alferdteen. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 1991. ISBN9781604738216. OCLC 775352334.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "History". The Renaissance Collaborative. Archived from the original on August 31, 2013. Retrieved Baronial 19, 2013.

- ^ Poe, Tracy N. (1999). "The Origins of Soul Food in Black Urban Identity: Chicago, 1915-1947," American Studies International. XXXVII No. 1 (February)

- ^ a b 'Ruralizing' the City: Theory, Culture, History, and Ability in the Urban Environment Archived September 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Reich, Steven A.: The Great Black Migration: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic

- ^ a b Anderson, Talmadge and Stewart, James Benjamin: Introduction to African American Studies: Transdisciplinary Approaches and Implications

- ^ Elaine), Anderson, Carol (Carol (May 31, 2016). White rage : the unspoken truth of our racial separate. New York, NY. ISBN9781632864123. OCLC 945729575.

- ^ Haygood, Wil (2013). The Butler: A Witness to History. 37 Ink. ISBN978-1476752990.

- ^ "August Wilson and The Migration to Pittsburgh". Hartford Stage . Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The The states, Regions, Divisions, and States Archived December 24, 2014, at the Wayback Car

- ^ a b "The Black Population: 2000" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Blackness Population: 2010" (PDF).

- ^ a b Population Division Working Paper – Historical Demography Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and Past Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990 – U.Southward. Census Agency Archived Baronial 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Yax, Population Sectionalisation, Laura G. "Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places In The The states: 1790 to 1990". www.census.gov.

- ^ Frey, William (2018). Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America. Brookings Establishment Printing. ISBN978-0815726494.

- ^ Toppo, Greg; Overberg, Paul (March 18, 2015). "After most 100 years, Great Migration begins reversal". U.s.a. Today . Retrieved February 19, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Further reading [edit]

- Carl Zimmer, "Tales of African-American History Found in Deoxyribonucleic acid", New York Times, May 27, 2016

- Arnesen, Eric (2002). Black Protest and the Great Migration: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford: St. Martin'southward Press. ISBN0-312-39129-iii.

- Baldwin, Davarian 50. Chicago's New Negroes: Modernity, the Great Migration, & Black Urban Life (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2007)

- Collins, William J. (November thirteen, 2020). "The Peachy Migration of Black Americans from the US South: A Guide and Interpretation". Explorations in Economic History

- DeSantis, Alan D. "Selling the American dream myth to black southerners: The Chicago Defender and the Groovy Migration of 1915–1919." Western Periodical of Communication (1998) 62#4 pp: 474–511. online

- Dove, Rita (1986). Thomas and Beulah. Carnegie Mellon Academy Press. ISBN0-88748-021-7.

- Grossman, James R. (1991). Country of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN0-226-30995-nine.

- Holley, Donald. The Second Great Emancipation: The Mechanical Cotton Picker, Blackness Migration, and How They Shaped the Modernistic South (Academy of Arkansas Press, 2000)

- Lemann, Nicholas (1991). The Promised Land: The Great Blackness Migration and How It Inverse America. Vintage Printing. ISBN0-679-73347-vii.

- Marks, Carole. Bye--We're Good and Gone: the great Black migration (Indiana Univ Press, 1989)

- Reich, Steven A. ed. The Nifty Black Migration: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic (2014), one-volume abridged version of 2006 three volume set up; Topical entries plus primary sources

- Rodgers, Lawrence Richard. Canaan Bound: The African-American Slap-up Migration Novel (University of Illinois Printing, 1997)

- Sernett, Milton (1997). Leap for the Promised Country: African Americans' Religion and the Keen Migration. Duke University Press. ISBN0-8223-1993-4.

- Scott, Emmett J. (1920). Negro Migration during the War.

- Sugrue, Thomas J. (2008). Sweetness Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Ceremonious Rights in the North. Random Firm. ISBN978-0-8129-7038-8.

- Tolnay, Stewart E. "The African American" Great Migration" and Beyond." Annual Review of Folklore (2003): 209-232. in JSTOR

- Tolnay, Stewart E. "The great migration and changes in the northern blackness family, 1940 to 1990." Social Forces (1997) 75#4 pp: 1213–1238.

- Trotter, Joe William, ed. The Keen Migration in historical perspective: New dimensions of race, class, and gender (Indiana University Press, 1991)

- Wilkerson, Isabel (2010). The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Nifty Migration. Random House. ISBN978-0-679-60407-five. OCLC 741763572.

External links [edit]

- "The Great Migration". Digital Public Library of America . Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Schomburg Heart'southward In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience

- Up from the Bottoms: The Search for the American Dream, (DVD on the Nifty MIGRATION)

- George King, "Goin' to Chicago and African American 'Keen Migrations'", Southern Spaces, December two, 2010.

- Due west Chester University, Goin' Due north: Stories from the Kickoff Great Migration to Philadelphia.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Migration_(African_American)

0 Response to "During the Great Migration, What Did the Term "Land of Hope" Refer to?"

Post a Comment